First-year students move earth…and bees

September 23, 2025

At the start of the school year, all 92 first-year undergraduate students got their hands dirty creating “topographical constructions” in the large wood planters beside the Architecture Building.

The Bachelor of Architectural Studies students were tackling the topic of land in their first studio. The project was called “Dirtwork” in reference to the 1960s land art movement and its earthworks. The aim was to broaden students’ perspective on construction, ground, and earth.

During the one-week exercise, eight groups took on the eight planters, which have been long-neglected. They carefully moved the earth inside the planters to transform them into sculptural environments that tell stories about earth, ground, digging, and surface.

“The essence of the work was to develop an affection for the earth in a personal way, to become more sensitive to how architecture touches down on the ground, to what happens when we build, and to earth’s transformative powers,” says Associate Professor Janine Debanné, the studio coordinator.

The teaching team included Adjunct Professor Adriana Ross and Instructors Amy Hetletvedt, Charline Ouellet, Gabriel Peña, and Bruno Silvestre.

Students were instructed that the earth had to remain inside the planters. However, as they began to make incisions using drafting tools and saws, they encountered a surprise. Wasps had built nests deep inside two of the planters.

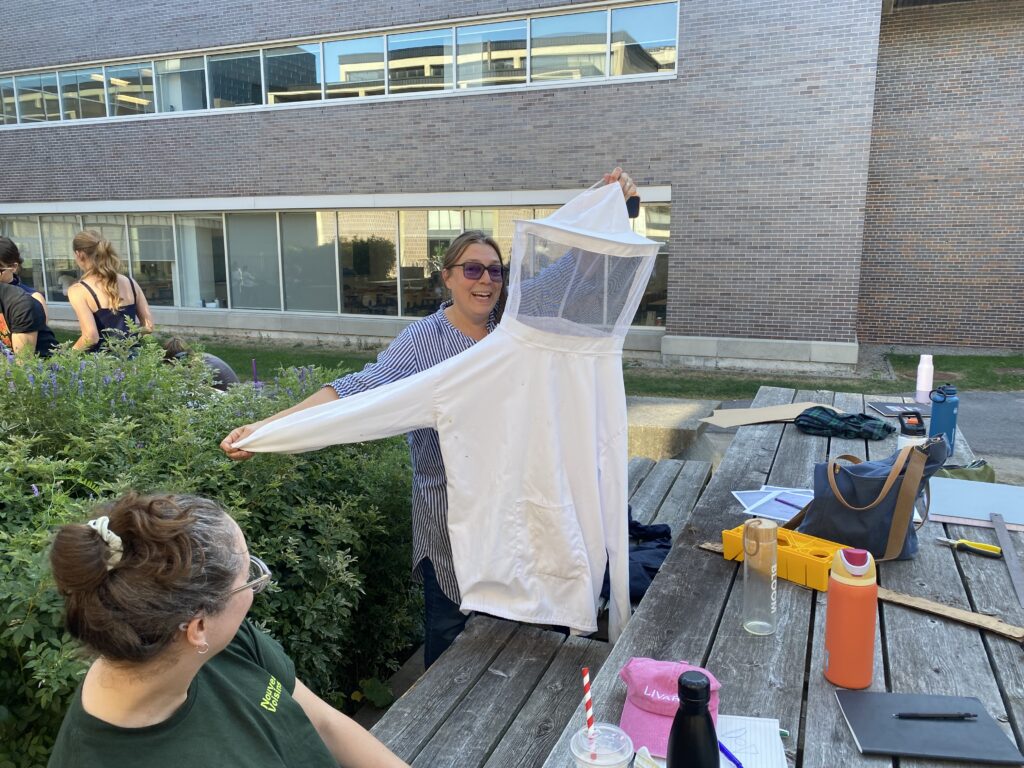

Although some students wanted to incorporate the nests into their projects, they needed to be removed for safety. Debanné returned to the site at night, wearing a makeshift protection suit, and dug out the affected planters and nests. Stung eight or nine times, she says: “It seemed right to pay a price!”

She adds: “The wasps taught us the important lesson that sites come with existing populations.”

After another nest was found and removed, this time with a proper bee suit, work began in earnest. The planters were heavily overgrown with end-of-summer grasses; students trimmed them with scissors and gathered trimmings for later use. Many placed them in their designs to create variations of texture.

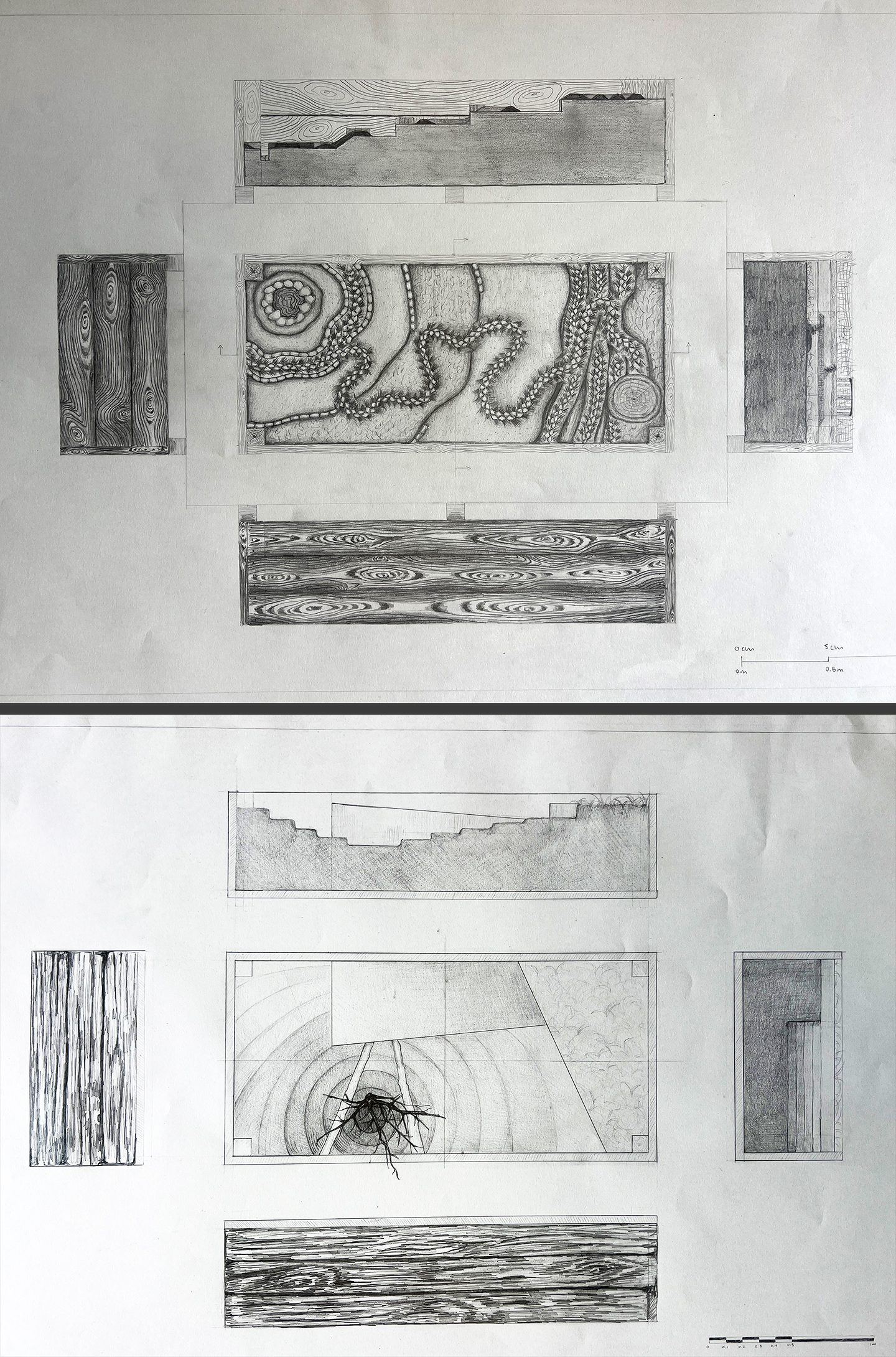

The project deliverables included the planter and a written and illustrated journal about their process.

Outside, some students dug, sketched, measured, cast bricks, made earth balls, and recuperated roots, while in the studio, others drafted the planters and studied the design intentions.

The work was supported by readings such as Dreaming in Dirt by BK Loren, William Bryant Logan’s Dirt: The Ecstatic Skin of the Earth, and writings by Joseph Rykwert, David Leatherbarrow, and Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer.

On that note, one team braided existing grasses all around a curved dug-out in their planter to secure the earth opening.

On September 18, students presented their projects. One group poured water to activate their planter-sized aqueduct that watered a plant that had been growing in the planter. Another reflected on the planter’s dimensions and construction, creating a grid of “earth bricks” while saving a field-pumpkin plant. Many grappled with the theme of reconciling human-made and nature-made environments.

“Working with the dirt, I realized that oftentimes we project our beliefs and ideas onto the material, as opposed to allowing it to inform those very decisions from the beginning,” said student Kaden Marshall.

The project brief referred to Robin Wall Kimmerer’s address to the General Assembly of the United Nations in 2015, and to her Indigenous biocentric worldview that proposes an expanded viewpoint that goes beyond humans’ actions of exploiting the earth for their benefit only.

The teaching team envisions a spring planting event during which students will return to their planter. Their topographical constructions will, they hope, become pollinator gardens for the summer season.

The studio’s theme of land reflects a new curriculum for the incoming first-year BAS students.

“The school is working to instill in our future designers a lively awareness of a shared planet,” explains Director Anne Bordeleau. “To that end, we are transitioning our curriculum so that it begins with land and building relationships, and moves through broad ecosystems, the public realm, and existing built environments.”

Meanwhile, in their new “Material Histories of Architecture and Conservation” course, taught by Dr. Bordeleau, these first-year students are looking at material stories and gaining awareness of the relationship between the materials architects specify and the land they are extracted from.

This week, they will continue to look at the earth as ground, land, and material. They are considering, for example, how as architects they can turn excavated earth, often considered waste, into a locally sourced biogenic building material.