M.Arch students prepare for climate change with collaborative specialization

Since 2022, master’s students at the Azrieli School of Architecture & Urbanism have been able to graduate with a Master of Architecture with a Collaborative Specialization in Climate Change.

“I don’t think we can ignore how deeply implicated our discipline is in the climate crisis, purely in terms of the material choices that we make and the energy that we consume through our buildings,” said Associate Professor Lisa Moffitt, who coordinates graduate studies at the school.

While the school does cover climate-related issues, “it is evident that students care and want to know more,” she says.

Architecture is one of 26 programs at Carleton University that can add a specialization in climate change to the degree by participating in a collaboration between the humanities, sciences, engineering, business, and public policy.

“It’s been an amazing experience,” said architecture student Madison Bolyea. “Speaking with people with different knowledge bases has expanded the way I see the world and design and possibilities.”

According to the Collaborative Specialization in Climate Change webpage, students “will examine the interconnected nature of climate change, including the impacts and potential options to manage within ecosystems, communities and institutions, and explore collaborative opportunities to address this global challenge.”

For Master of Architecture students, this means taking two classes in climate change as approved electives, and their thesis must be related to climate change.

“What the collaborative element offers is rather than taking four separate courses — a science course, an anthropology course, a public policy course, and an architecture course — you’re taking a course in which we’re having conversations that are cutting across those disciplines,” explains Dr. Moffitt.

“We can offer up insights about how we think about similar issues, but from our respective disciplinary vantage points,” she says.

Of about 20 Carleton students currently taking part, 11 are architecture students. Cole Marotta is one of them. “The solution is more complicated than I thought it would be,” he acknowledges.

“It is important for students to get a sense of their agency in the face of the climate crisis,” says Director Anne Bordeleau. “This work takes place in our courses — with attention to materials, site, or land, or by thinking of buildings from cradle to disassembly,” she says. “The specialization offers greater insights into the complex and multifaceted questions surrounding climate change and environmental justice. “

The professors for the specialization typically come from four of the participating faculties and change annually.

This year, Moffitt represented the Faculty of Engineering and Design, with the other professors drawn from the faculties of Public and Global Affairs, Arts and Social Sciences, and Science. Students are exposed to a broad range of topics and the differing ways climate change is understood.

Moffitt introduced students to distinctions between embodied and operational carbon, outlined the fundamentals of passive design, and illustrated how stringent thermal comfort expectations drive energy consumption. She also introduced students to principles of regenerative design and low-embodied carbon building materials.

The school’s Assistant Professor Jerry Hacker gave a guest lecture focusing on his award-winning work on plastic-free construction.

Inger Weibust, an assistant professor of international affairs, teaches a course on climate change and international relations within her department and brings that perspective to the collaborative program.

“I start with explaining the collective action problems at the heart of climate change,” says Weibust, who studies how governance structures affect our ability to tackle environmental problems.

“I really want students to understand the collective action problem — that we’re not here because people are particularly bad or particularly selfish. We really require a solution with a very high degree of international cooperation.”

When asked how architecture students react, she says, “I think they were kind of shell-shocked by my presentation because they had never heard the issue discussed in those terms.”

Architecture students, she notes, have brought rich examples to discussions from field trips and design-build projects in Ottawa. These are context-specific and bring questions of adaptation to group discussions.

Danielle DiNovelli-Lang, an assistant professor of anthropology in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, says she hopes the complexity revealed by ethnographic discussion will prevent the simplistic jumping in to design a building as a fix.

“I find the architecture students are really keen to learn how to pay attention to the specifics of a situation, to note what people really want and need, from the bottom up instead of top down, which gels nicely with what I think anthropology can offer,” she adds.

“They also tend to have experience visiting actual places and appreciating the differences they see there.”

Keegan Metheringham, one of the architecture students doing the specialization this year, explains that they have a weekly seminar group discussion with outside experts. For example, he took part in one led by a wildfire operations specialist. Another was with an architect advancing the innovative use of engineered wood in construction, while another considered the experience with carbon pricing in South Africa.

“While I’m learning the tools and methods of architecture, it’s a great time to also think about adaptation and how we’re going to move forward,” he says.

Learn more about the Collaborative Specialization in Climate Change here.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

Cole Marotta, Hannah Baird, Madison Bolyea, and Keegan Metheringham are among the students taking the specialization and currently working on their theses. The diversity of approaches reveals the breadth of issues and opportunities for architecture to engage with the climate crisis.

In Search of Good Fire: A Design Journey

Keegan Metheringham

Through journals, maps, drawings, models, photos, and video recordings, this thesis explores the relationship between fire-adapted ecosystems and the built environment, seeking ways to design and adapt to wildfire.

Fire is a natural component of many of Canada’s ecosystems, supporting biodiversity and habitat regeneration. However, the threat that wildfires pose is growing. In 2023, wildfires burned more than 15 million hectares of forests and grasslands — more than twice the previous record set in 1989. Over 250,000 Canadians live in areas of high wildfire risk. To better understand this challenge, I trained and worked as a wildland firefighter and prescribed fire technician, learning about fire behaviour and the environmental conditions that influence its intensity and spread.

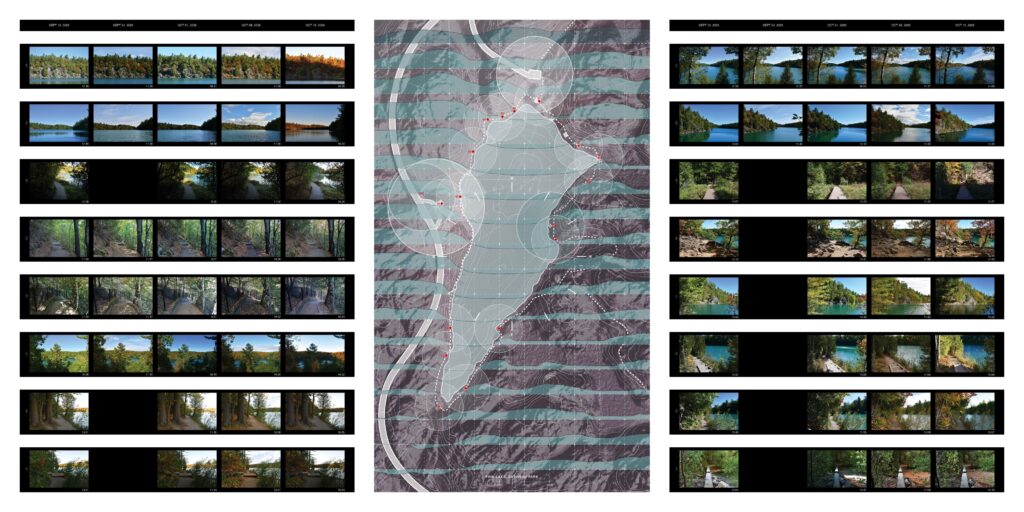

Pink Lake as a Scientific Record and Ecological Archive

Madison Bolyea

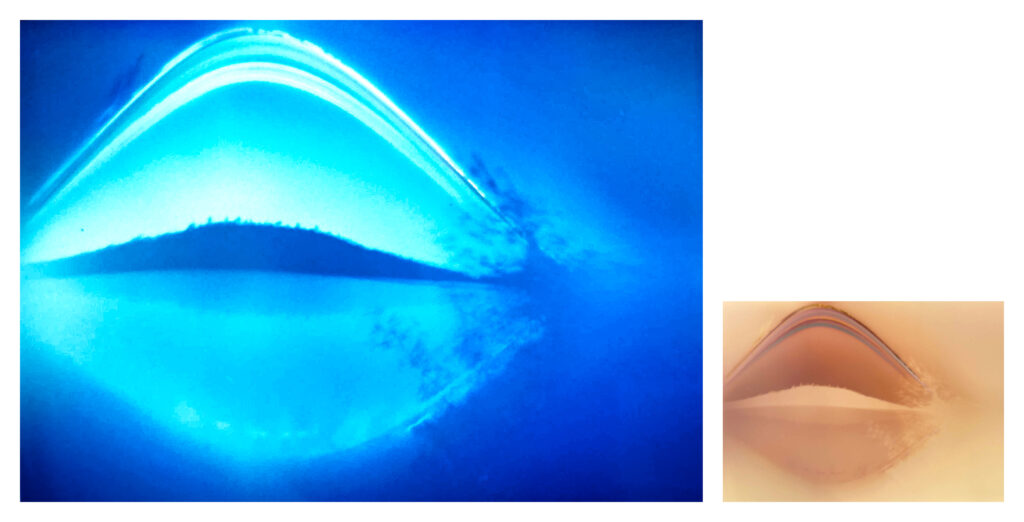

This study of Pink Lake investigates how time, memory, and environmental processes can be documented, interpreted, and represented through architectural and spatial methodologies, including drawing, mapping, photography, and fieldwork.

Pink Lake in Gatineau Park is a rare meromictic lake; the geological makeup of the lake basin and surrounding terrain prevent its layers of water from mixing. This stagnant aquatic environment and anoxic lower waters allow sediment to settle along the lakebed, forming distinct stratified layers that have accumulated to form a continuous record of atmospheric and geological change over the last 10,600 years. However, as erosion and eutrophication accelerate under human pressure, the lake’s fragile equilibrium has become increasingly vulnerable to ecological collapse.

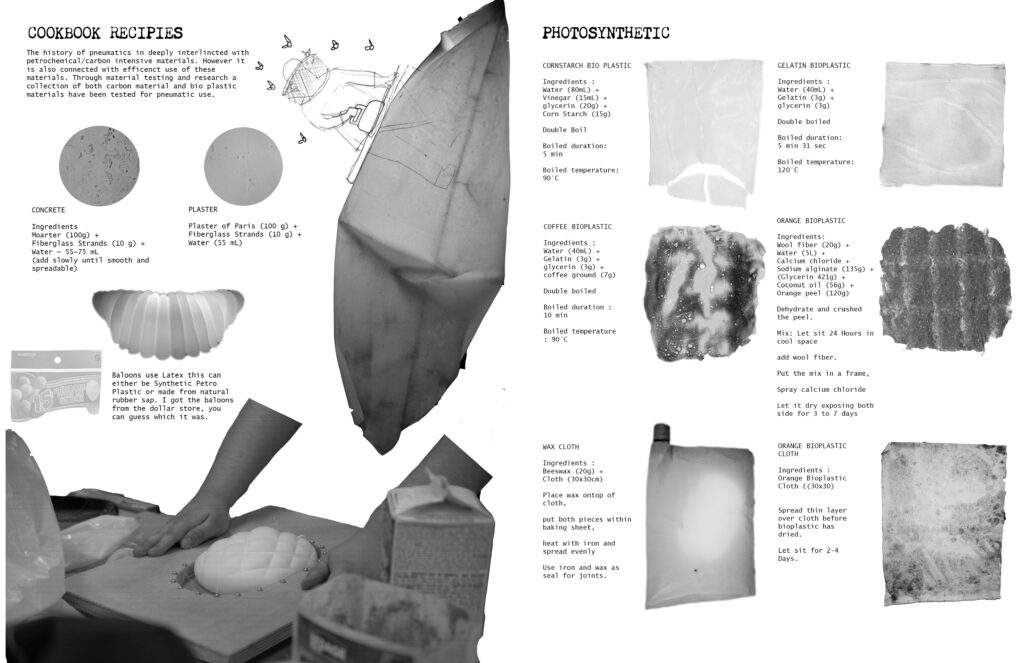

Reinflating Pneumatics

Cole Marotta

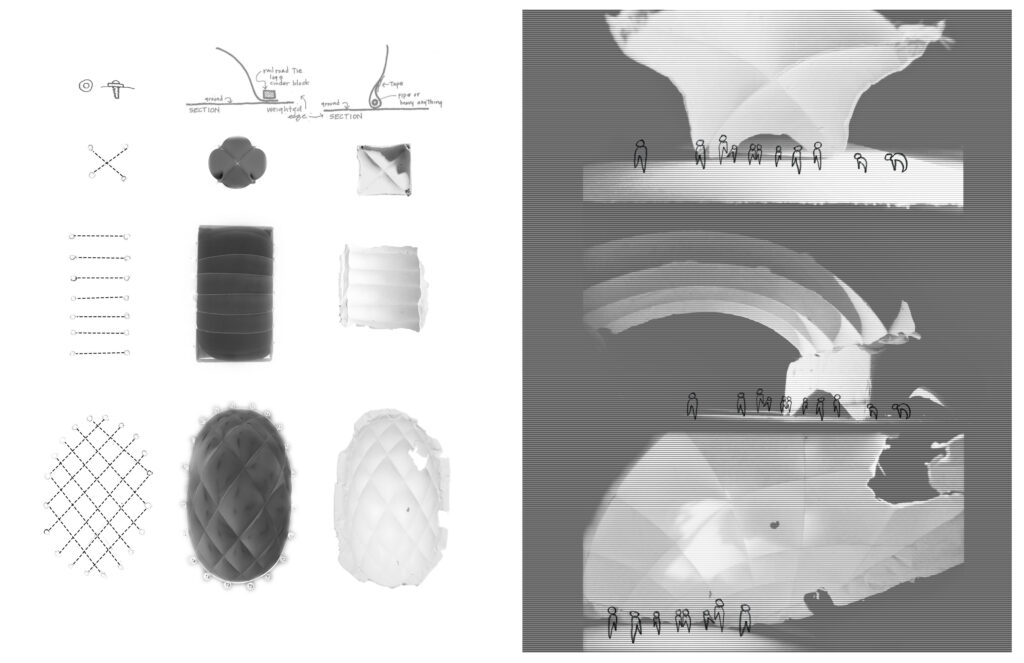

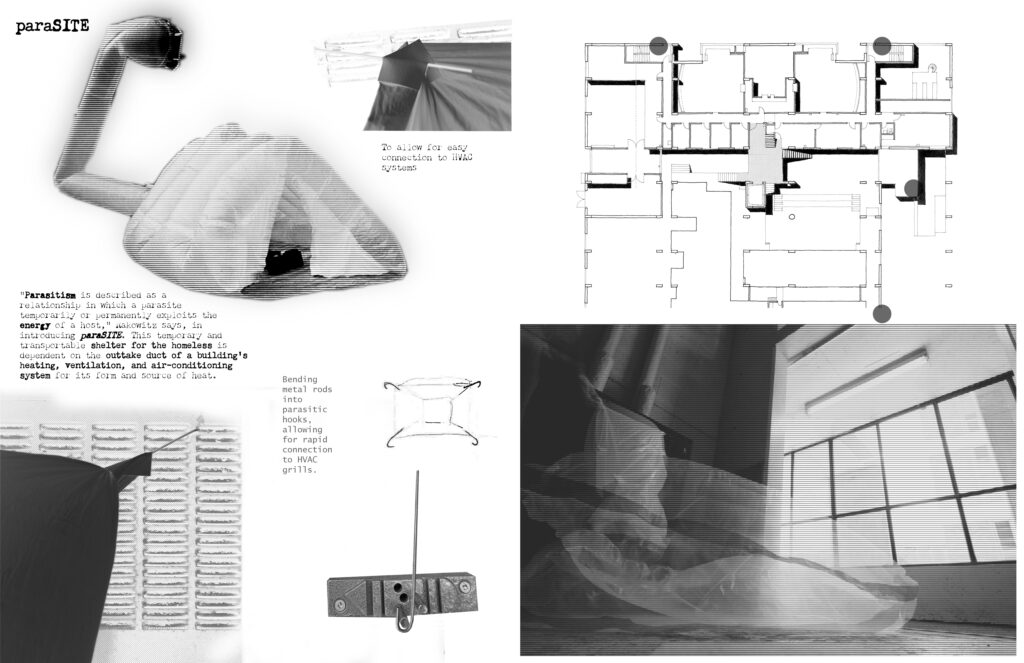

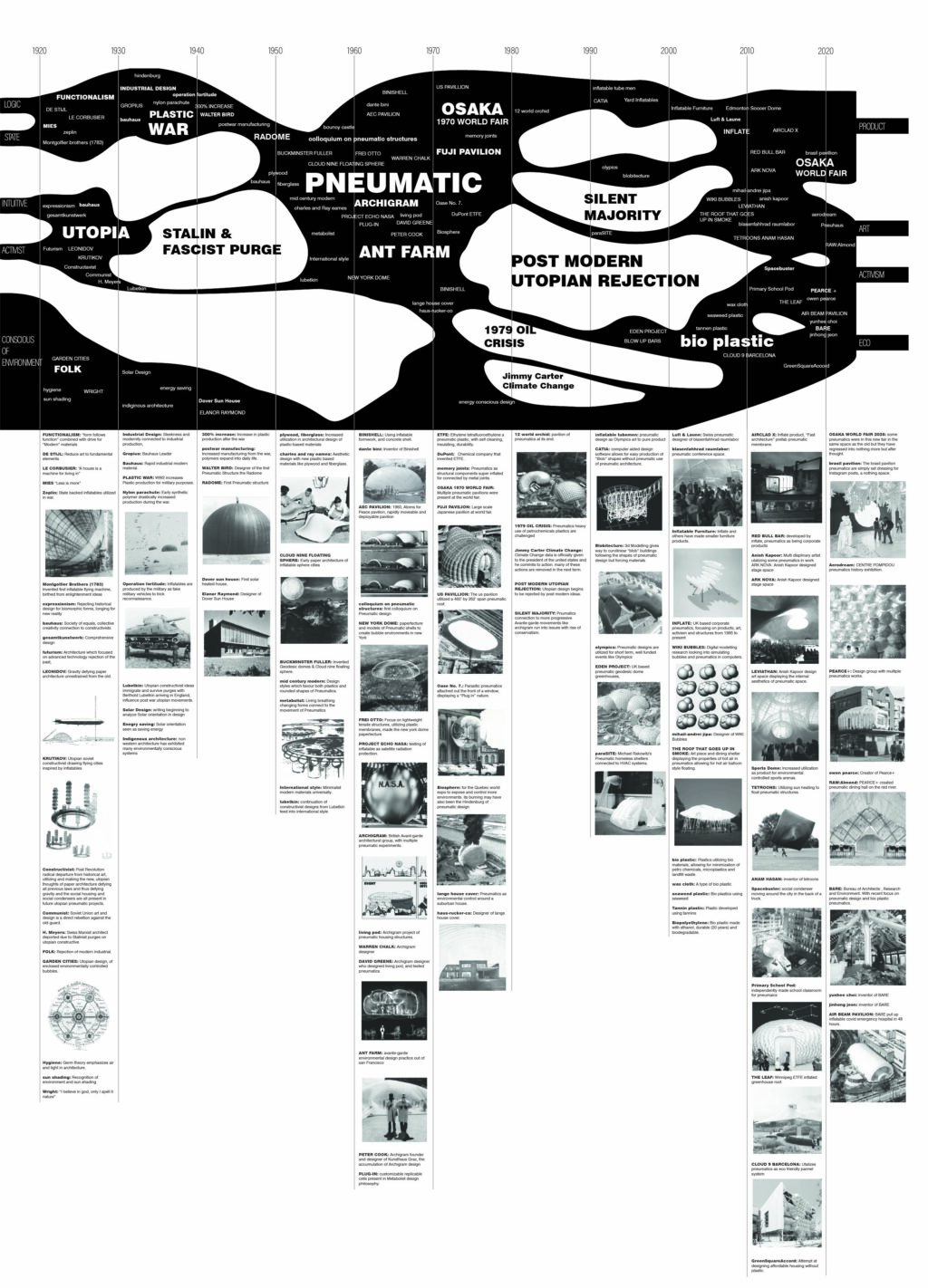

In the 1960s and ‘70s, numerous groups, including Ant Farm and Archigram, championed pneumatic architecture for its advantages: rapid assembly and disassembly, light weight, material efficiency, low cost, ease of transport, and the novel aesthetics of semi-opaque, curvilinear spaces.

Today, mobility, efficiency, and affordability are more critical than ever. But how can these structures assist in climate response while embodying issues of the climate crisis: petrochemical dependence, microplastic pollution, and the energy demands of HVAC systems for temperature control and inflation?

Contemporary designers experiment with bioplastics and exhaust air. By comparing new and old guides to pneumatics, what might be revealed about the changing relationship between architecture, technology, and the environment?

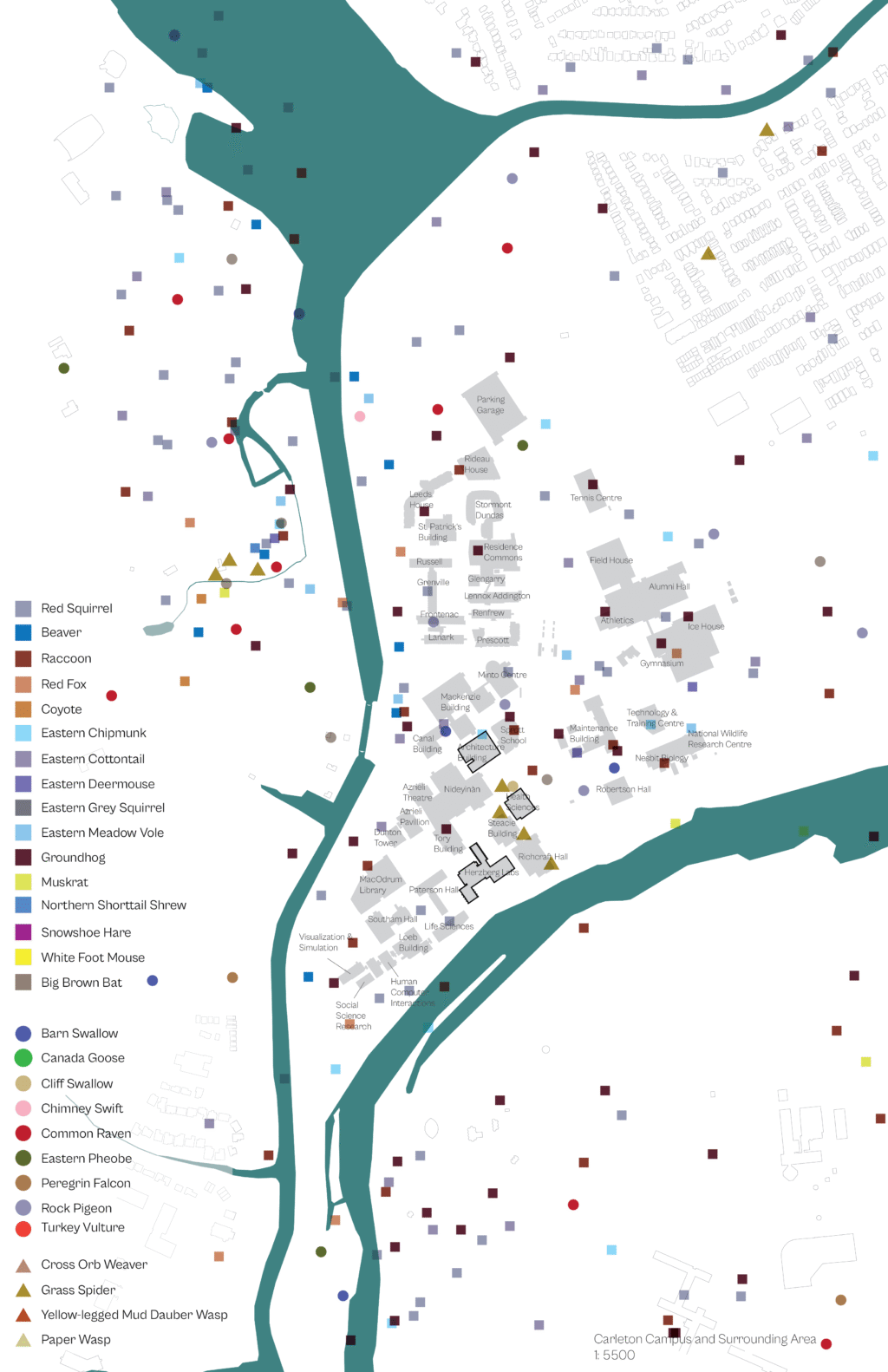

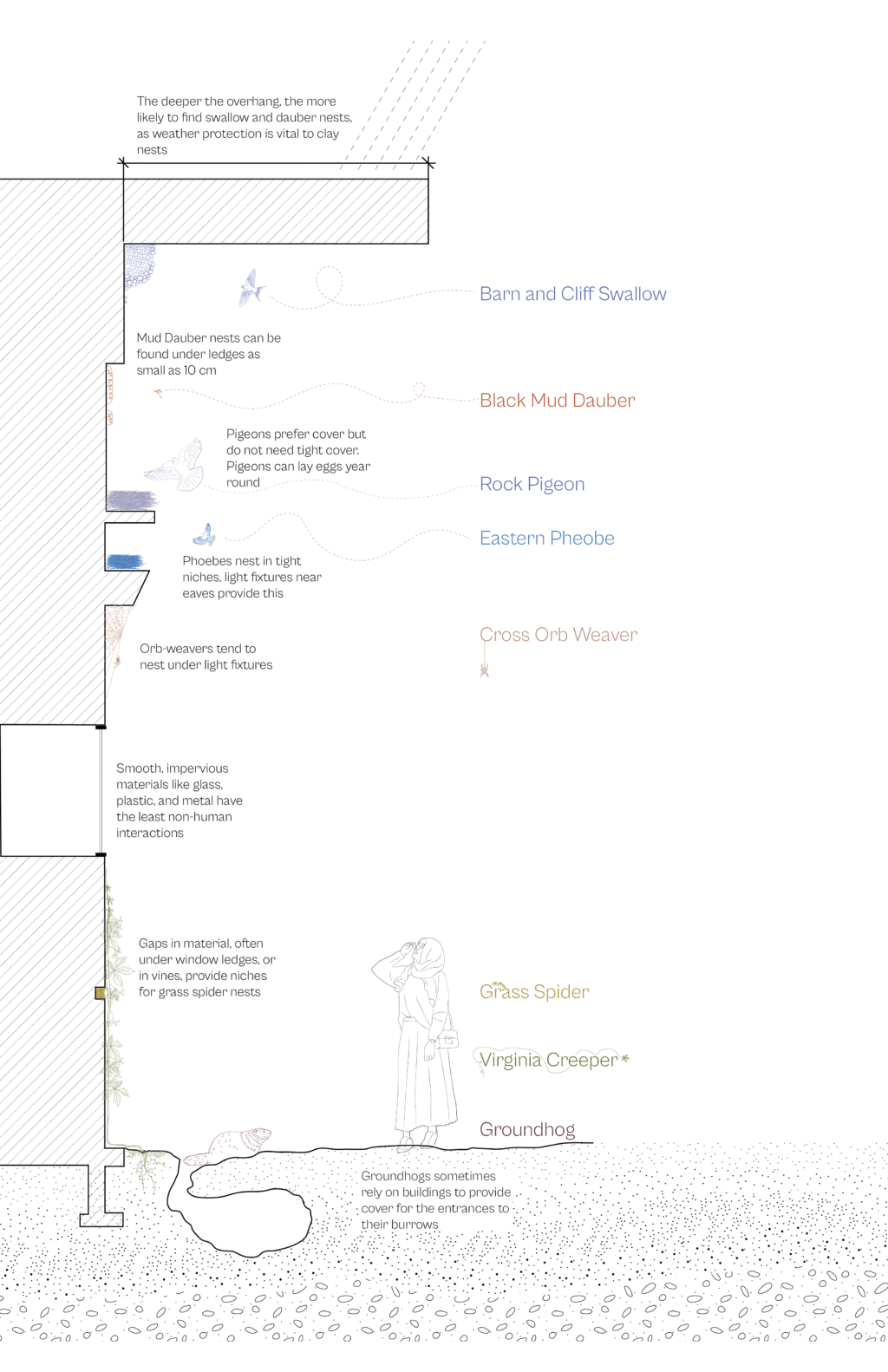

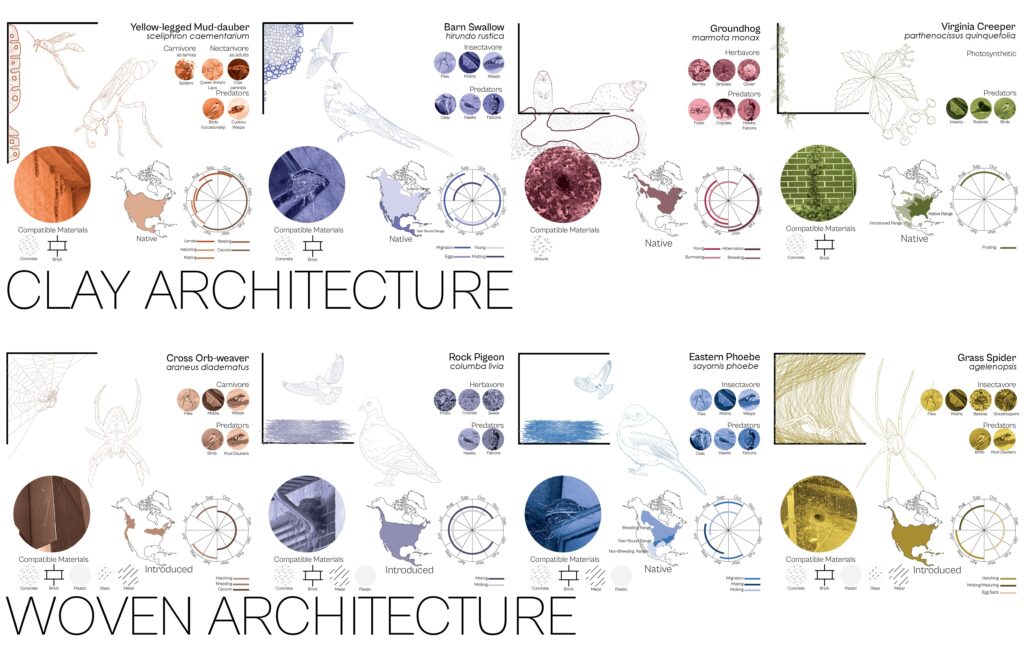

Birds, Bees, and Buildings: Towards a Co-authored Ecology of Care

Hannah Baird

This thesis investigates the built environment of Carleton University as a site for co-authorship between humans and non-humans. It asks how design can decenter the human experience by affording ecology spatial agency and acknowledging other species’ expertise. Through site analysis and mapping, the project first identifies human-non-human proximities and how the two architectural practices intersect. Cataloging non-human adaptations of urban form and studying animal-built structures, it develops strategies to position non-humans not only as users but also as co-designers whose contributions shape our built environment. Addressing pervasive colonial extractivist structures and humanity’s disproportionate environmental impact, the research challenges Western conceptions of human exceptionalism and separation from nature. It proposes tactical interventions that invite active modifications by our non-human counterparts.