Cattails to coffee: Students build “speculative assemblies” with regenerative materials

December 2, 2024

Master of Architecture student Emma Monfette donned hip waders to gather cattails which were then dried and pressed to form an insulating wall for the Advanced Building Systems workshop course taught by Assistant Professor Jerry Hacker.

Her classmate Mikhala Gibson made bricks from coffee ground waste. Student Theo Jemtrud milled a standing dead tree for a proposal aiming to use “the fewest materials possible.”

“Analog methods have intentionally been used to explore notions of slower, more meaningful interactions with materials and assemblies,” says Hacker. “Textbooks have largely been traded in for crowbars and tools.”

The fall 2024 course, titled Speculative Assemblies, is exploring regenerative and non-toxic building materials, systems, and ecologies.

–

Emma Monfette

This assembly is composed of materials that are local to Canada and abundant in all provinces; harvested and gathered locally from Carp, Ont. All the materials are non-toxic and safe to return to the earth after their life cycle in the assembly. The cedar structure is assembled using traditional joinery and dowels. Cattail leaves and stems are compressed into a rigid insulation board that is vapor-permeable and fire-resistant. Exterior cedar shingles on an angled horizontal strapping system allow water to shed away from the interior, also allowing the wall to dry out. The floor is layers of rammed earth, acting as a large thermal mass. Without the use of any adhesives, mechanical fasteners, or plastics, this wall assembly proposes a new way of approaching building materials and techniques.

Mikhala Gibson

The materials chosen to build the Coffee Wall include coffee, clay, hemp, lime, sand, and wood. The coffee used to make the bricks was taken from coffee waste produced on the Carleton University campus. This was done to explore how the waste material of coffee grounds could be used as a building material rather than being sent to a landfill. The bricks were laid using a lime mortar to avoid using cement mortar. The insulation panels were made with hemp and lime. Finally, some of the wood used was also waste found on campus.

Theo Jemtrud

My speculative assembly aimed to use the fewest materials possible, which included hemp, lime, and deadwood that I milled and harvested. All the wood is from the same tree, and dowel connections are used at every joint. The hempcrete acts as the insulator, and the wood acts as the structure for the wall, floor, and battens. Offcuts from the milling process are used for the exterior siding, and tongue and groove boards are used for the interior finishes. Overall, the assembly helped me understand how things come together within a real-world scenario.

–

There are about 50 students in the class. Half are in the first year of the two-year master’s program, and half are in the second year of the three-year M.Arch.

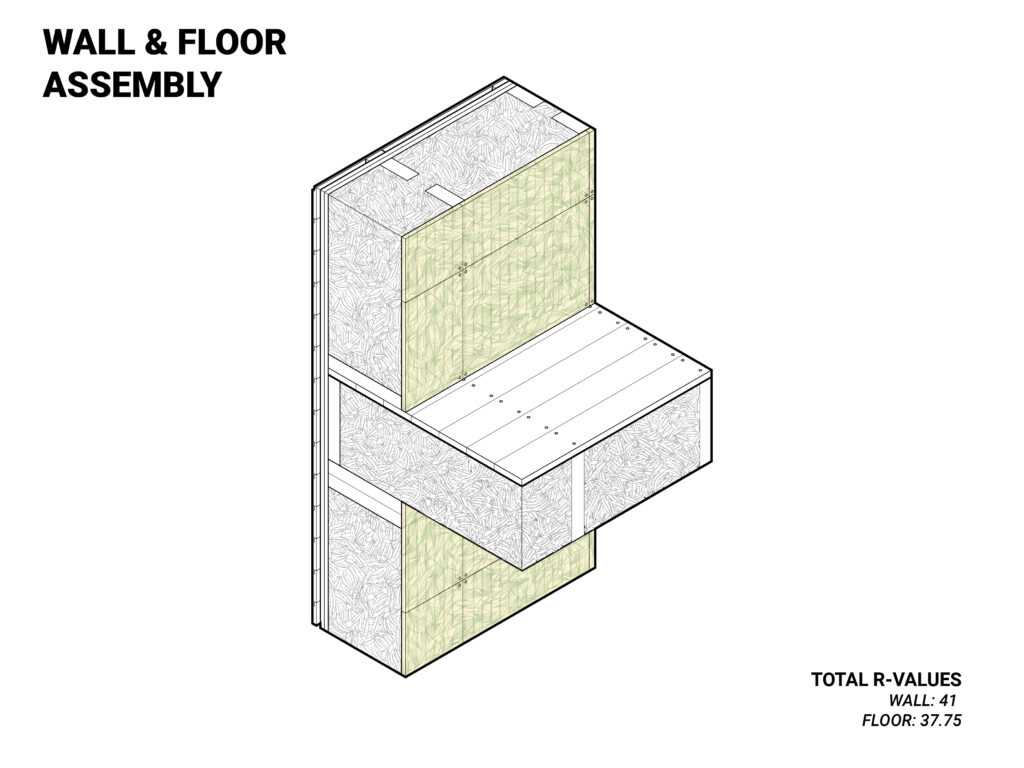

The students began by studying and taking apart conventional construction assemblies. Then, they were tasked with making a new speculative wall and floor assembly. As Hacker states, “If we want sustainability to become ‘flourishability’ we need to think and act differently.”

The course requires students to consider the social and environmental effects of the full life cycle of the materials — from initial gathering to assembly, in use, to eventual reuse or decomposition.

“This assignment pushed us to use our knowledge of wall compositions to a level that considers the environmental impact of our building practices,” says Monfette. “Having the opportunity to build a 1:2 scale model of our concepts allowed us to explore methods of connection, and the craft involved.”

The materials used by students in lieu of present construction methods, which are often petrochemical derivatives, include hemp, lime plaster, rammed earth, pine resin, denim, cork, cob, clay, coffee grounds, leaf mulch, cellulose, beeswax, and bioplastic.

–

Daphne Stams

When prompted to explore bio-material alternatives to contemporary construction materials, I conducted three experiments. The first was for a water barrier replacement, for which I used melted beeswax to make an impervious barrier over plywood. Next, I blended different paper materials (a book, cardboard boxes, and magazines) and dried them to make recycled cellulose insulation. My third experiment was with bioplastic, where I tried various recipes and arrived at a potato-starch-based recipe. I used a thinner, more flexible recipe for the subfloor layer and then combined a harder recipe with paper pulp to create solid cladding.

Madison Bolyea

Palletable Partition is a completely regenerative, biodegradable, locally sourced, nontoxic wall and floor assembly that challenges typical construction methodologies. Commonly wasted byproducts of modern industrial practices are integrated with additional natural materials to create an assembly suitable for cold weather climates while reducing waste and lowering carbon emissions. Such wasted byproducts include the heat-treated wood pallets which make up the majority of the finishes and structural elements, chicken feathers that act as insulation, and pine tree resin mixed with pine needles to create an impermeable interior finish.

–

Hacker’s course combines hands-on practical assignments and working in the school’s wood shop, with lectures about climate change, embodied and operational energy, and principles of cold weather design. It looks at material extraction and processing, the hidden costs and damaging effects of present materials and methods, and the alternative of potential healthy material ecologies.

“If we are serious about addressing the climate crisis and imagining a post-carbon future, now is the only time for a significant change in the way we build,” he writes in the course outline.

“We need to re-evaluate what constitutes an acceptable material in the places we occupy and in the air we breathe, and what we take from and put back into the single environment that we have to ‘sustain’ ourselves.”

As the final technology course in the school’s sequence, students have a foundational technical knowledge, opening the way for other questions to be asked, he says.

Students are primarily learning how to constructively question the established means and methods used in the design and construction of contemporary buildings in Canada, while simultaneously interrogating alternate possibilities founded in bioregional and regenerative approaches and processes.

–

Jeremie Lafleche

TreeForm is a speculative assembly inspired by the components of a tree. The stick framing serves as the primary structure in the assembly and is meant to represent a tree trunk. The wooden dowel fasteners act as roots and branches that join the assembly together using both friction and gravity. The cork performs the task of regulating temperature differences through the assembly and protecting it from external conditions, much like bark on a tree. The pine resin and maple leaf cladding act as the first defense against the elements, providing a hydrophobic barrier akin to that of a canopy of leaves on a tree.

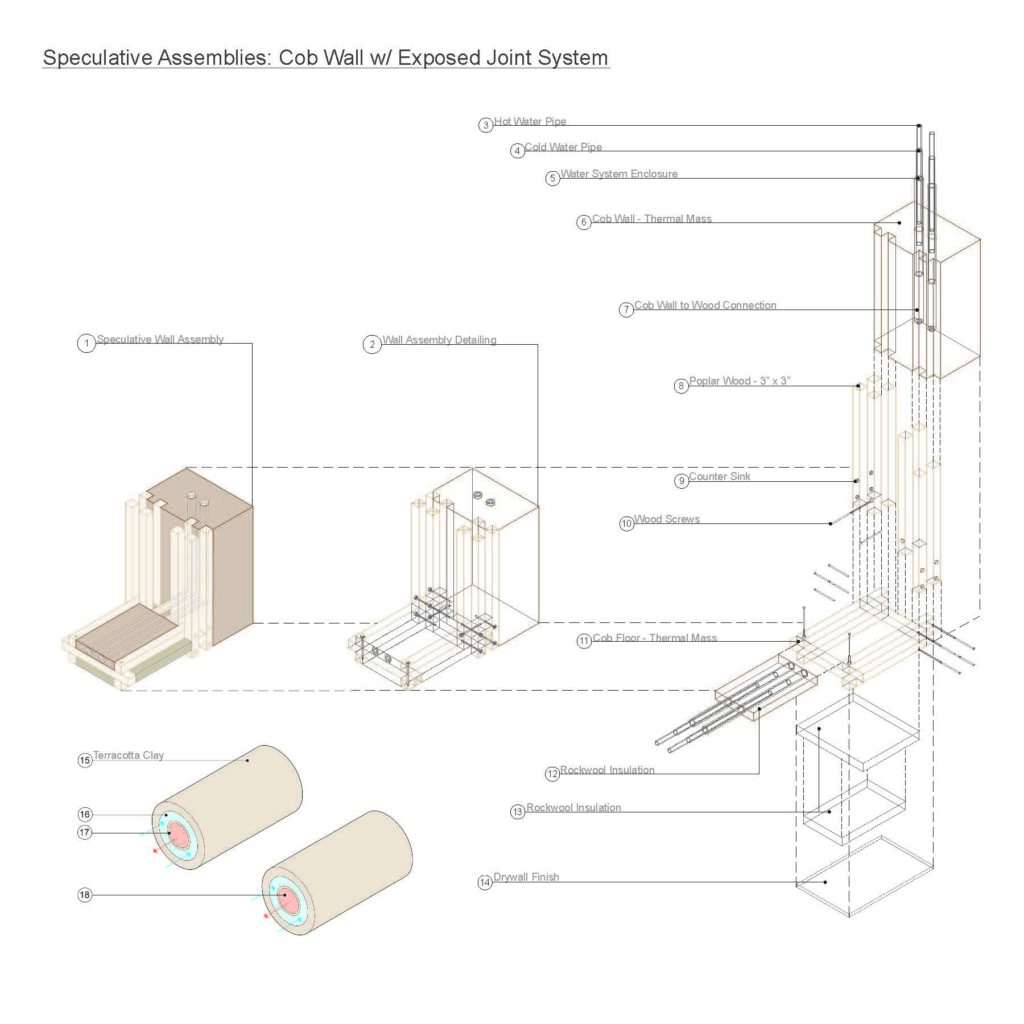

Simon Martignago

This speculative assembly explores a sustainable, modular wall system integrating regenerative materials and passive energy solutions. Key components include untreated wood, cob, terracotta, copper piping, and Rockwool insulation, chosen for their low embodied carbon, recyclability, and circularity. The cob acts as thermal mass and cladding, paired with terracotta and copper pipes for efficient heat and water management, leveraging off-gassed steam from a nuclear-powered system for passive heating. The assembly emphasizes ease of disassembly, adaptability, and lifecycle sustainability, embodying eco-friendly principles while supporting energy-efficient, regenerative design.