Work by students helps First Nation transform ex-residential school

By Maria Cook

March 19, 2024

The Muskowekwan First Nation of Saskatchewan is generously acknowledging the role of Carleton University architecture students and professors in advancing its vision to convert a former residential school to a place of healing.

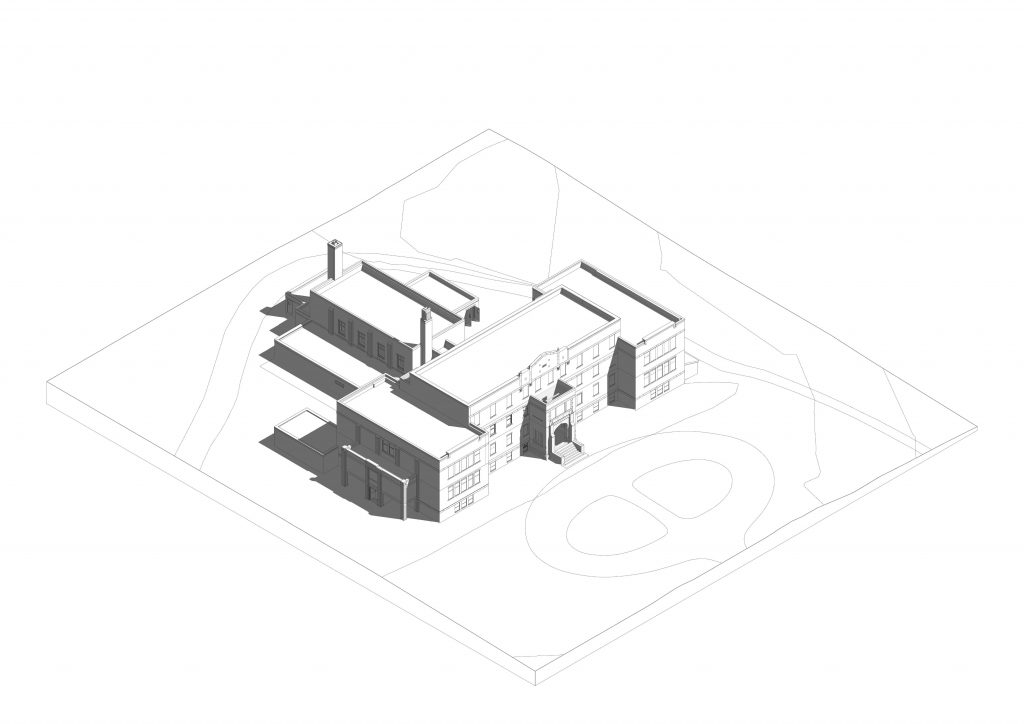

Notably, a digital model prepared by students will help guide the transformation of the vacant Muskowekwan Indian Residential School. Students have also explored possibilities for the adaptive re-use of the building, contributing to the refinement of objectives for the project. It is the last standing residential school in Saskatchewan and has since become a National Historic Site.

Last month, the Muskowekwan First Nation’s Chief and Council, the Historical Site Advisory Committee, and members of the Nation announced that it had retained the team of Brook McIlroy Architects (Indigenous Design Studio) with ERA Architects, along with engineers and cost consultants, to undertake work on the structure.

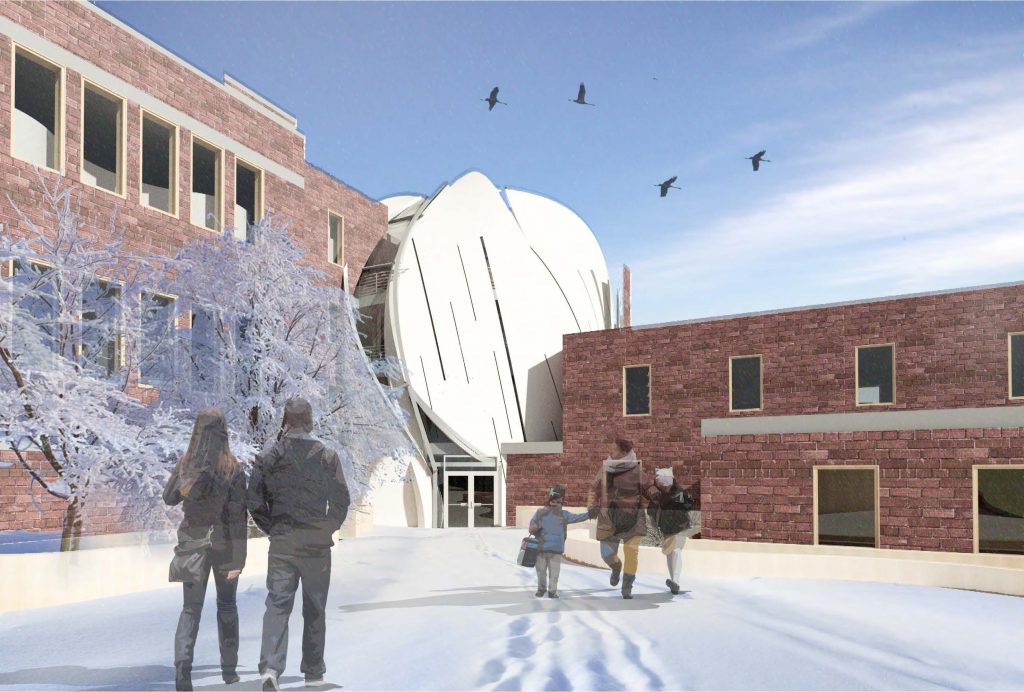

“Their work will greatly assist the Nation in achieving its vision for repurposing the former Muskowekwan Residential School from a site with a history of trauma to a place that contributes to healing, wellness, cultural learning, commemoration, and creativity for the benefit of present and future generations,” said the Muskowekwan First Nation’s announcement.

The announcement noted that since 2019, the Azrieli School of Architecture & Urbanism (ASAU) and the Carleton Immersive Media Studio (CIMS), a research lab affiliated with ASAU, have “provided ongoing architectural design and heritage conservation advisory services in support of Muskowekwan First Nation’s vision.”

The Muskowekwan First Nation also highlighted the valuable resource created by CIMS that will continue to support development of the project: “The CIMS lab has produced a comprehensive digital building information model (BIM) that will technically inform the work of the Brook McIlroy team.”

Professor Stephen Fai, director of CIMS, led the documentation project in partnership with the National Trust for Canada and the Muskowekwan First Nation. He calls it an honour and a responsibility.

In 2019, Dr. Fai travelled with a crew from CIMS to record the as-found conditions of the site, located on the Muskowekwan First Nation territory, about 150 kilometres northeast of Regina.

“Muskowekwan First Nation is located very close to the Qu’Appelle Valley, where I spent some time as a young adult. It’s a place that I still hold dear to my heart.” he recalls. “I knew of the community during my time there, but I didn’t know them. When I was asked by Lyette Fortin to return to that sublime place and explore the possibility of supporting the community, I felt a personal connection and a moral responsibility.”

The students who visited the site were Ken Percy, Jessica Mendoza, and Daniela Veisman, plus Anna Turrina, a visiting scholar from Italy.

Turrina, Veisman and Mendoza went on to describe the process in an article, Tracing a Site of ‘Difficult Heritage’ on the National Trust for Canada website:

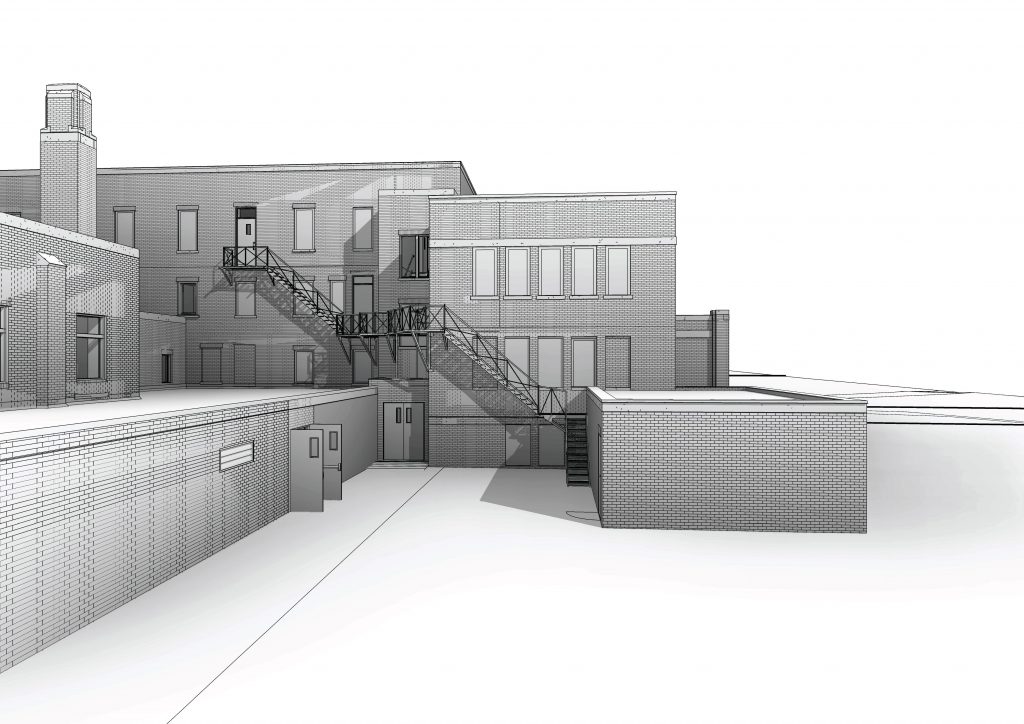

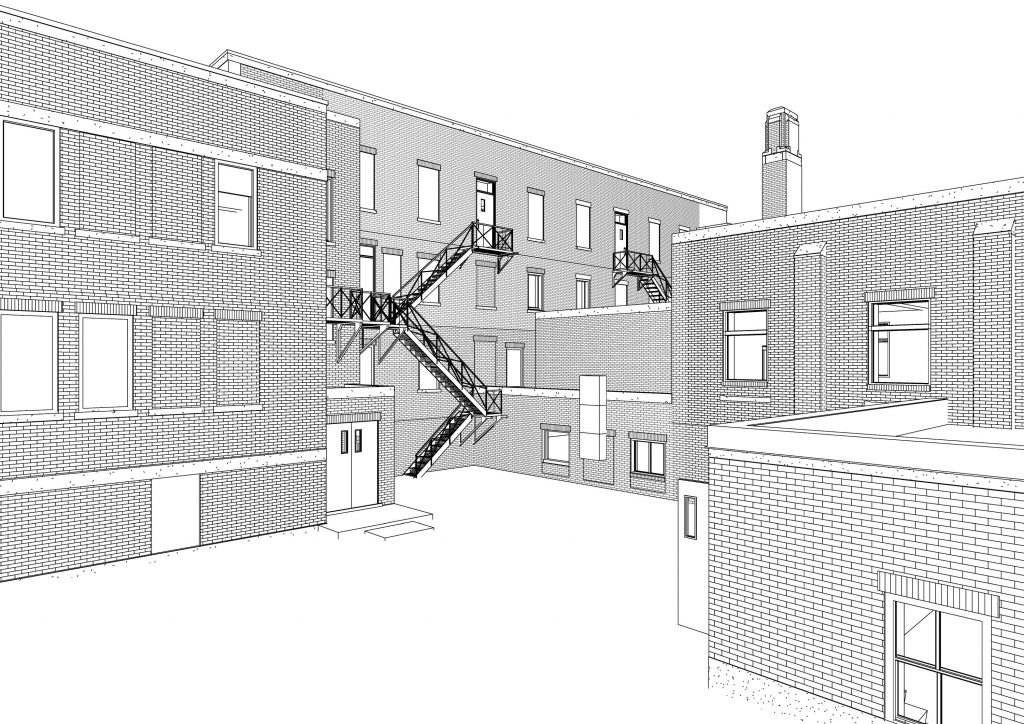

The Muskowekwan Band Council granted permission to document the premises using a laser-scanning camera device to capture detailed 3D information known as a Point Cloud. For more complex architectural details and character-defining elements, the profiles and textures were also captured using photogrammetry to digitally record an even higher level of detail.

Back in the research lab, hundreds of 3D scans and photos were combined in Revit (3D modeling software produced by AutoDesk) to generate a highly accurate comprehensive digital model of the building and grounds of the Muskowekwan Residential School.

“We scanned the entire building and did some photogrammetry as well,” says Fai. “We used that to build a very accurate Building Information Model. That’s what’s being passed on to the consultants. It will be the basis of their study for the rehabilitation. Since the model is geometrically accurate, they’ll be able to use it to develop their design proposal and do everything from calculate square footage to visualization.”

Members of the community have visited CIMS on two occasions to review the progress of the model.

“As a school, we are committed to creating meaningful and non-extractive relations with various communities, but also to acknowledging both the legacies and atrocities that our presence on the land carries,” says ASAU Director Anne Bordeleau.

“When we think of ways in which we can meaningfully participate in this acknowledgement of the truth to move towards reconciliation, the ongoing relationship with Muskowekwan First Nation is an indication of how such activities might unfold, and how we might conduct ourselves when engaging in this healing work.”

The project was supported in its entirety by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Partnership Program, specifically New Paradigm / New Tools for Architectural Heritage in Canada (895-2015-1018).

PhD student Simone Fallica, a researcher at CIMS, has worked on further developing the building information model. “Beyond its mere technical aspects, the project has offered me an invaluable lesson on the role of architectural practice as a deeply human endeavor, undertaken by human beings together with other human beings,” he says.

“I am grateful to have played a small role in the framework of the process of healing and reconciliation underlying the MSK project because that helped me become aware of the scars and open wounds of the survivors and witnesses who carry the memory of what happened in the school.”

The collaboration between the school and the community dates to 2018, the year the National Trust for Canada put the Muskowekwan Residential School on its list of the Top 10 Endangered Places in Canada.

While the school opened in the 1880s, the current school building was constructed in 1930 after a fire in the previous structure. The replacement was designed in Collegiate Gothic style, featuring a Tudor-style archway and ornamental stone trims on the façade. A central driveway leading to the front steps is lined with rows of elm trees planted by students more used to prairie grass and wetlands.

It was part of the system of federally supported residential schools located across the country, which sought to assimilate Indigenous children by isolating them from their families, cultures, languages, and traditions. The site operated until 1997, one of the last such institutions to close in Canada.

Fai first visited Muskowekwan in November 2018 with National Trust Executive Director Natalie Bull and Adjunct Professor Lyette Fortin.

“That meeting was very moving,” he says, noting that it coincided with an event that the Centre for Truth and Reconciliation was sponsoring. “There was a group of 12 women from the community that told their stories. It spoke to the multi-generational impact that the residential school has had on the community. If we can do anything to mitigate that damage or to help in healing it — I feel it’s an obligation.”

After meeting with Elders and other community members, Fai decided to use his lab to make a detailed 3D model, while Fortin made the residential school the focus of the 2019 third-year Conservation & Sustainability studio. Shortly after, Adjunct Professor Jim Mountain inherited the studio.

The undergraduate students in the studio were Lauren Liebe, Khadija Waheed, Spencer Lapko, Hassan Hannawi, Vanessa De Alexandris, Hope Good, Arkoun Merchant, Patrick Bustin, Kseniia Beliaeva, Claire Bodrug, Merissa Lompart, Carlee Wale, Teagan Hyndman, Kaleigh Mackay, Luis Panchi Galvan, and Danica Mitric.

They researched the history of the school, studied the surrounding landscape and climate, and compiled archival images and copies of the original architectural drawings. The studio produced nine design concepts to transform the former residential school into a training centre, museum, archive, and memorial.

“I learned much about the history of the site and the importance of protocol and sensitivity when it comes to any design interventions,” says Arkoun Merchant, now a Master of Architecture student at ASAU.

“It is great to see that the tireless efforts by Muskowekwan First Nation over the past five years has led to a collaboration that will keep the community at the heart of any design decisions.”

Teagan Hyndman is now an architectural designer and heritage professional with ERA Architects and will be traveling to Muskowekwan First Nation in April as part of the Brook McIlroy-ERA team. She expects to help with drafting, on-site documentation and heritage consulting.

“Working on this project as a student fundamentally changed my perspective on heritage conservation,” says Hyndman. “I was used to seeing conservation practices used for places that are highly regarded, not for places of immense suffering.

“It’s been a little surreal to have been introduced to this project when it was a dream for the Muskowekwan community, and to now be professionally involved with work I’ve been following and advocating for years,” she says.

“I’m honestly just in awe by the resilience of the community, having pushed for this work to be done for so long, despite how painful it is to do so. They really deserve for the site to finally become a place of healing, and I’m grateful to still be involved with seeing that happen.”

Meanwhile, Danica Mitric ended up writing a, 8,500-word dissertation, The Potential of Muscowequan Residential School: The Challenges of a Creative Adaptive Reuse of Sites of Trauma by the Impacted Community, while pursuing a master’s degree at Nottingham Trent University in the United Kingdom.

“I have worked in heritage conservation for over forty years, and, without question, this has been the most meaningful and important project I have ever been associated with,” says Prof. Mountain.

“Everyone from Carleton has been touched so deeply and emotionally by our collective experience,” he says. “The 2019 studio work has never really ended! For the past five years, we have remained dedicated and committed to seeing the Muskowekwan vision for this site.”

About the Project

The Muskowekwan First Nation has retained the team of Brook McIlroy Architects (Indigenous Design Studio) with ERA Architects, Hanscomb Cost Consultants and ALFA (electrical), HDA (mechanical), and BBK (structural) engineers.

This multi-disciplinary team with knowledge of Indigenous culture and experience with cultural heritage projects will provide architectural design, cultural landscape conservation, engineering assessment, building heritage conservation, museological, and cultural planning services to Muskowekwan First Nation from February to November 2024.

All work will be guided by Muskowekwan First Nation’s Council, elders, survivors and knowledge keepers in adherence with protocols developed by the project Historical Site Advisory Committee (HSAC) for conducting the business of this important project.

Muskowekwan First Nation undertakes this project in honour of all families – past, present and future whose generations of children were taken from them and placed in this facility, many to never return home again. “The impacts of this history have been profoundly felt intergenerationally, and this project to achieve our longstanding vision is an essential part of our Nation’s ongoing healing process.”

The site is located on Muskowekwan First Nation territory approximately 150 kilometres northeast of Regina, within the Touchwood Agency Tribal Council area and is within Treaty 4 Territory which encompasses the original lands of the nêhiyawak (Cree), Saulteaux, Dakota, Lakota, and Nakoda, and the homeland of the Métis/Michif Nation.

Indigenous children from across Treaty 4 Territory and elsewhere attended the facility with children from nearby First Nations – Muskowekwan, Kawacatoose, George Gordon, Yellow Quill, Fishing Lake, Kinistin, and Day Star – all being forcibly compelled by Canada’s policies to be in attendance there.

Muskowekwan First Nation worked collaboratively with Parks Canada to achieve designation of Muscowequan IRS as a National Historic Site in 2021.

The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (Winnipeg) has provided ongoing advisory support and research for the site’s history. University of Saskatchewan (Anthropology) and University of Alberta Institute of Prairie and Indigenous Archaeology has provided research expertise in to-date, locating 35 unmarked graves at the site.

(Source: Muskowekwan First Nation)