Students contribute design ideas to The Ottawa Hospital

Fourth-year architecture students have contributed speculative design ideas to The Ottawa Hospital for a planned new facility on the edge of the Central Experimental Farm.

The collaboration between the hospital and the Azrieli School of Architecture & Urbanism is an example of how Azrieli students gain relevant experience and engage with the community on timely issues. The collaboration continues in the 2020-2021 academic year.

Fourteen students took part in last winter’s undergraduate studio, led by Prof. Federica Goffi. The project was to develop a Welcome Centre where volunteers and staff provide information and help to patients and families. It is also a place to buy gifts, order services, and pay for parking.

“The most interesting thing about this project is probably its timing,” says Wendy Yuan, one of the students. The group visited the hospital’s Civic campus in January and the General campus in February. On March 18, Carleton university moved teaching online.

“As we transitioned into online studio in March, we also altered our design in consideration of the hospital’s crucial role in this ongoing pandemic,” says Yuan. “We shifted our focus from the general well-being of the users of the space to infection control of potential COVID patients. Being able to propose a solution to a present-day problem, and to communicate with different stakeholders of this project adds profound meaning to our design, and validates the reasons for which we study to become architects.”

The new $2-billion hospital adjacent to Dow’s Lake will replace the current Civic campus on Carling Avenue. Planning and design are underway. Construction is set to begin in 2024.

The students produced eight visionary projects that explore the links between personal wellness and the spaces of healthcare. (Read more about the studio after the descriptions, including how to obtain the project booklet.)

The Oasis: Biophilia

Connor DeJonge and Jillian Weinberger seek to make calming moments of beauty in spaces more usually associated with stress and illness. Transparency brings the outdoors indoors. Inside the building, vertical tubular glass lattice structures pass through the floors, becoming light-filled “terrariums” “like rays of greenery beaming into the building’s core.” A two-level road system allows people to enter from the ground or lower level. An additional entrance on the ground floor can serve as an isolated “pandemic” entrance.

Pathways to Wellness

Katie Wilson and Melissa Brady begin their project with the idea of a journey, both to visit loved ones and toward healing. To preserve trees and address the challenge of a slope, they designed an enclosed pathway, that incorporates a covered drop-off area and a ramp extending to the Welcome Centre. The ramp has rest areas and plantings. A dramatic roof structure echoes the movement of the paths leading to the information desk, a focal point. Views connect to the outdoors.

Symbiosis

Arkoun Merchant and Kito Ballentyne note the importance of nature and sunlight in human well-being. They propose a dramatic structure that refers to a tree in its vertical spreading form and creates the Welcome Centre space. Its branching form supports bacteria-resistant fiberglass fabric panels to make a light-filled environment. A recessed lounge offers a private nook to destress. The scheme includes the use of partition walls to separate high-risk and general patients to minimize infection.

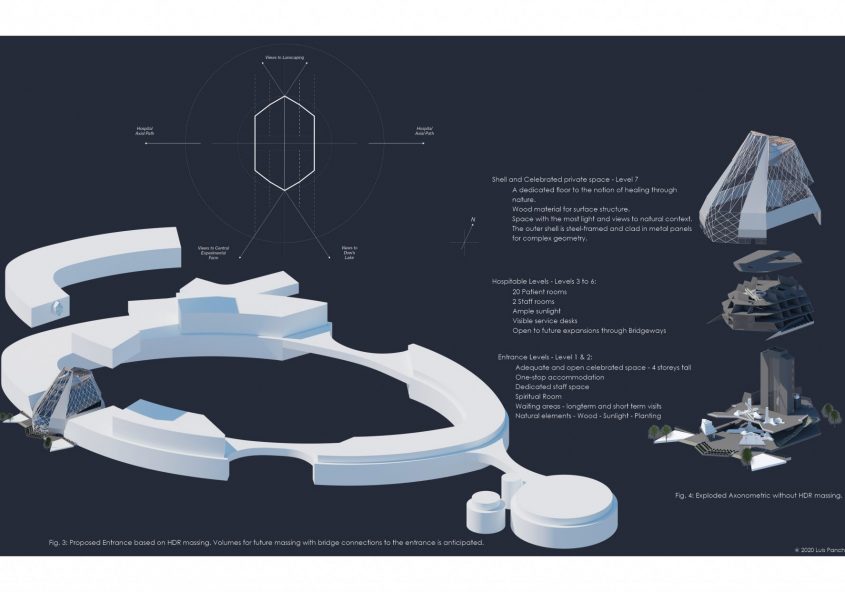

The Oculus – Purposefully Incomplete

Luis Panchi Galvan and Hassan Hannawi imagine the Welcome Centre as a distinct, self-contained building joined into the ring-shaped building suggested by the master plan. Its strong vertical form and sloping walls give identity. Any future vertical expansion of the hospital is accommodated by its height. The title “Oculus” comes from its design to bring in light. The multiple floors vary to accommodate the different functions of the Welcome Centre and to receive healing light.

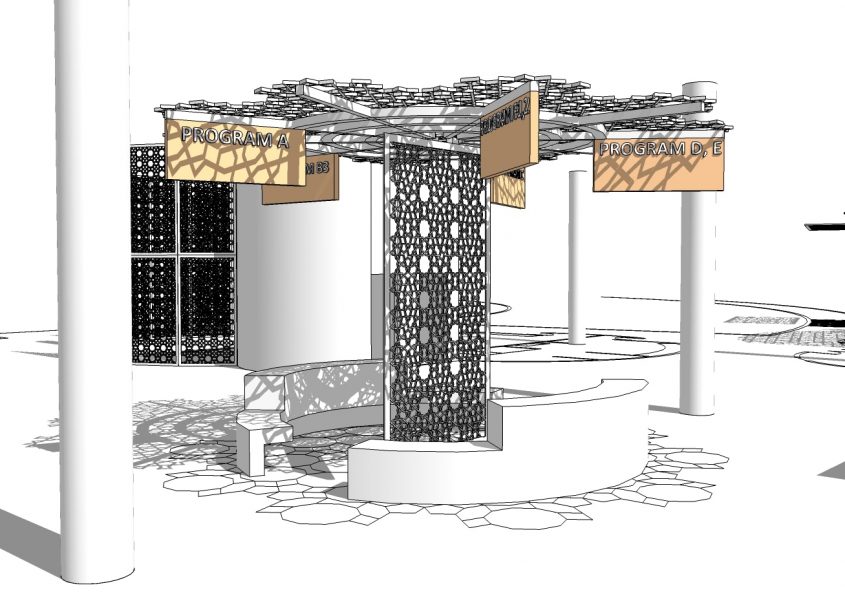

Perforated Screens: To Conceal and To Reveal

Wendy Yuan proposes floating the different functions of the Welcome Centre in a series of curved pods of activity within the large overall space. Perforated screens articulate the enclosures and ceilings, allowing light and air and providing privacy. A central information desk is a point of reference for visitors and the surrounding pods. A compass on the ceiling above the desk is part of a way-finding system of pattern and colour that extends to the floor and corridors.

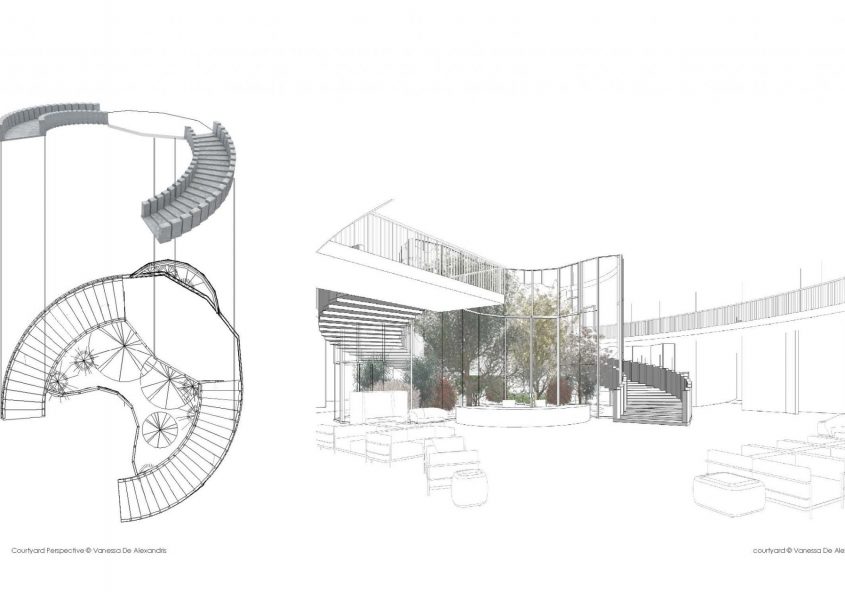

To Guide – To Heal – To Comfort

Nicole Coutinho and Vanessa De Alexandris design a Wellness Centre made lively by colour, material, and shape. A wall of coloured glass proposes that the architectural enclosure be art, rather than contain it. The possibilities of colour as “chromatherapy” are suggested. Curving walls and staircase define smaller spaces adjusted to the scale of a person or small group within the centre. Built-in alcoves can switch from storing equipment to housing a patient in extraordinary circumstances, with a foldable wall barrier for privacy.

A Journey to Healing

David Bastien-Allard and Nadia Maarouf accommodate the Welcome Centre with a series of rectilinear spaces for the functions, held together by a large central volume providing access and orientation. The enclosure is a lattice of wood, transparent glass, and light. Water from the roof is channeled through the structure – imagined as a tree sculpture – to be collected and filtered before use in the building. The spaces for people under the tree sculpture are a healing place, like sitting under a tree in a park.

Ataraxia

Merissa Lompart names the project with the Greek word “Ataraxia,” meaning extreme calmness. In her proposal, plants, light, colour, and a wood structure are used to make intimate spaces adjusted to the scale of visitors and patients. The geometry of the wood structure provides rhythm and unity. Way-finding is assisted by colour. Plant rooms provide a space for visitors or patients to plant seeds or a small plant and nurture it for the duration of their stay.

A booklet titled HOSPITAL(ITY) IN ARCHITECTURE: TOH’s New Civic Campus Welcome Centre +ADAPTIVE ARCHITECTURE: From exportable to ADAPTIVE DETAILS documents the projects. It is dedicated “to healthcare workers and volunteers around the world, working beyond the call of duty under the COVID-19 pandemic.” To request a copy, please contact Prof. Goffi at federicagoffi@cunet.carleton.ca.

“Hospitals are paradigmatic examples of buildings in need of frequent technological improvements and adaptations to new and unplanned circumstances – as the COVID-19 pandemic makes evident,” writes Goffi, who has published articles on the relationship between health and architecture.

“The construction of a new hospital may be seen as an opportunity to foster the conception of new details that may be adapted to the remodeling projects of existing hospitals,” she adds.

The studio focused on details and defining the qualities of “hospitable” architecture. The projects built on the vision of The Ottawa Hospital and its Volunteer Resources and Program Planning departments.

“Proper details are critical in defining our sense of place and providing comfort and care for residents, visitors, volunteers, and medical staff,” says Goffi. “Nevertheless, often, medical facilities are designed to best house machines rather than people.”

According to the hospital, the Welcome Centre will be comprised of the main entrance where incoming patients will be oriented to hospital services. Additionally, it will house a series of specialty hubs, where services are provided on a one-to-one basis with patients or families. These are repeated at three elevator lobbies to serve the three broad disciplines of inpatient care, ambulatory care, and rehabilitation.

Using the demonstration master plan prepared by HDR architects, the students located and designed a Welcome Centre. In this context as a place of arrival and departure, they considered the materials, details, sequences, and physical architectural constructions. In addition to daily functions such as registration, information, and orientation, they also took into account the sensory experience.

As noted by Goffi, “to investigate the architecture of hospitals as a body of sensorial and cultural resonance, beyond mere concern for visuality, one has to deal with the complex wired experience of visual, tactile, olfactory, and aural stimuli facilitating human interaction and the providing of care and health services.”

“The notion of ADAPTATION – the topic that we elected for our studio investigation… into the design of contemporary hospitals – became visible in real-time,” she says.

In response to the pandemic, Goffi asked students to address questions such as how to compartmentalize the Welcome Centre during a pandemic or adapt hospital corridors – traditionally non-adaptable spaces – in times when the full capacity of the hospital is exceeded.

They also considered “extra-to-ordinary” features such as a dedicated staff entrance, drive-through areas for testing and drop-off, and vehicular circulation on two levels or the two sides of the hospital.

The plan had initially been to present the project at the hospital, but instead, final reviews took place on Zoom, with participation by hospital managers and invited critics.

Students worked beyond the end of the term by about four weeks to complete the projects to their satisfaction, adds Goffi. “They went beyond academic requirements, showing a real sense of care and a desire to contribute to this field with selfless dedication.”

The faculty and students of the Azrieli School of Architecture & Urbanism express their sincere gratitude to all The Ottawa Hospital staff who provided guidance. Special thanks go to Sherri Daly (Manager, Volunteer Resources) and Michelle Currie (Manager of Program Planning) for their advice throughout the project.