Fragments of wood from Isaacs Harbour, Byward Market, and Luskville

Artist: Sheryl Boyle

This tile was created by slicing collected wood fragments from across Eastern Canada and assembling the slices into a layered landscape of stories. Each piece of wood tells a unique story. The tile’s commentary about adaptive reuse and social justice is significant to the Azrieli School of Architecture & Urbanism and Associate Professor Sheryl Boyle’s course, Recycling Architecture in Canada and Abroad (ARCH 4206).

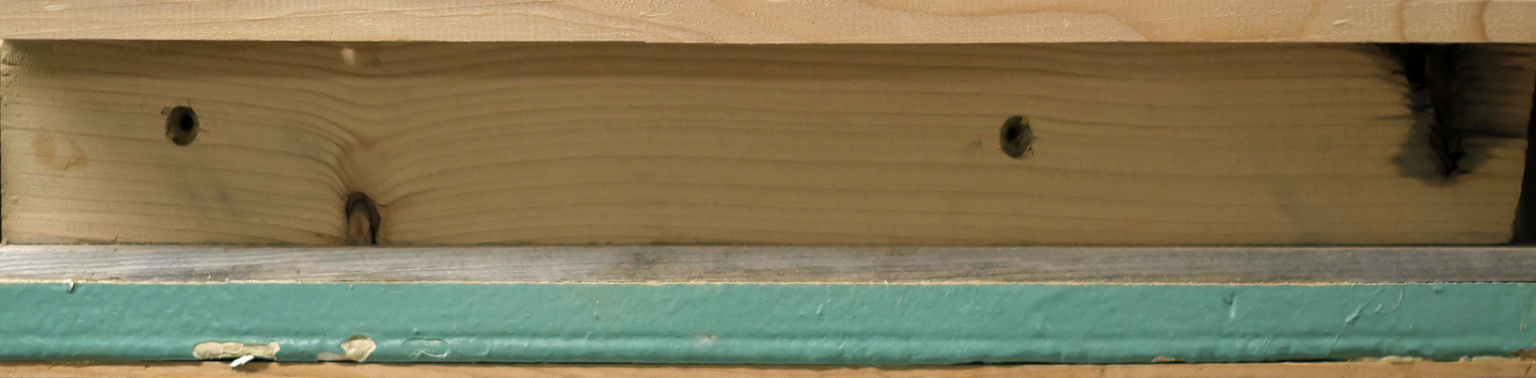

The lower blue-green wood fragments are from a house in Isaac’s Harbour, Nova Scotia. One segment had veneer overlaid on the front before being painted, and the other fragment was painted pine. Isaac’s Harbour was initially Mi’kmaq habitation. The first colonists were Black Loyalists who arrived in 1817 after a gale destroyed their settlement in Country Harbour, Nova Scotia. Webb’s Cove on the east side of Isaac’s Harbour (now called Goldboro) is named after Isaac Webb and his family due to their hospitality in this remote area. This confluence of First Nations and Black settlers made up the first settlement patterns in this remote cove of Nova Scotia. The first white settlers arrived in the early 1830s. The pine planks are from an early 1900’s house in Isaac’s Harbour. The grain of the wood recorded the rain, winds, and atmosphere of the East Coast community. It was painted on the front face the colour of the ocean and the sky.

The pine pieces are from 30-foot-long floor joists in Boyle’s house in the Byward Market, built in 1895. The ends of the joists were cut from the building during a porch restoration in 2019 and left in a heap for landfill until Boyle salvaged them. They have visible iron stains from the hand-forged nails, pockmarks from hammers, and honey tones from years of aging alongside the coal chute to the basement. They are part of a construction system of first-growth pine timber floor joists and stacked pine timber walls held vertically with heavy rib-like strapping. This construction system is reminiscent of the houses built by canal boatbuilders at the turn of the century. A light green fragment of decorative trim discovered in the basement is also visible.

Wood from an early 20th-century carpenter’s toolbox, found at the side of the road in Luskville, Quebec, has also been assembled into this landscape of stories. The wooden toolbox had two upper trays, a space for two saws held in with wooden latches in the lid, and marks from the various iron tools inside the box. It smelled musty from sitting abandoned in a basement. Rounded and scuffed, the edges showed signs of wear and use. Craftspeople were critical in the transformation of wood to plank to building, which was mostly done by hand at the turn of the century. Tooling marks are left on the material, and indications of its environment and atmosphere are visible in its grain.

This tile provides a commentary on adaptive reuse, its potential and power, and how it might be misused or disregarded. It’s important to understand the life of buildings and materials after their intended first use and how that can relate to questions of appropriation and issues of equity, diversity, and inclusion. This tile aims to address the participation of materials in social justice and injustice and inspire awareness of the surrounding historical context and ethics of making.